AI generated art — and in fact, AI generated everything, not just images — has burst onto the scene to the bewilderment of an unprepared world. It’s art — but is it really?

It’s enough to break your brain.

While it’s true that the U.S. Copyright Office has stated they won’t copyright purely machine made “art”, in point of fact, AI art generation tools do not generally produce usable results without such input or guidance, and the Copyright Office has allowed copyrighting of work whose creation was assisted by AI. Purely machine made “art” is actually extremely rare. The rest of the time, a human is driving. It’s like those walking baby dolls Mattel used to make: they could only walk if you kept them upright and drew them forward by holding their hands.

It should be noted that the author of this article is not a lawyer, and that fac ts presented in this article should not be construed as legal advice.

Further, the opinions of this writer do not necessarily represent those of Six Degrees of Geek, its editor, or its management.

Yes, But Who Owns the Copyright, If Anyone?

There is considerable discussion of who owns the copyright to such images but for the most part the IP lawyers either ignore the fact that the AI’s cannot generate output without specific human guidance, or that AI is already everywhere in art creation tools like Photoshop, Ableton, and even Google Docs but that nobody questions the authorship of work made with those tools simply on the basis of the tools themselves.

To use the Photoshop analogy again, it is obviously possibly to load a copyrighted image into Photoshop, make a small change to it, and then save that image back out as a new image, and still violate the copyright of the original artist. And yet, even here it is not the tool at fault, but the user.

Some of these IP lawyers are just reading back disclaimers made by the tools’ creators into their public statements. They are looking for a note of authority — any authority — that they can cite on the subject, and then rattle off a series of follow-on statements as though the source of their musings was a valid one. I would keep in mind that lawyers are always reading these things the way they would when preparing for court with a potential client, and they frequently don’t care which side of the question they fall on so long as they might get paid. It’s reflexive. They can’t help it.

It doesn’t help that in general, the law suits against software publishers like Stability AI, the creators of Stable Diffusion, grossly mischaracterize the operation of the software. Yet, they proceed with the suit hoping that the court, in its ignorance, will simply take their word on how it works. It’s a “throw it against the wall and see what sticks” approach.

It’s going to be a complicated battle. First, the plaintiffs are in different countries. LAION, the creators of the LAION dataset upon which Stable Diffusion, Dall-E, Midjourney and others are based, is in Munich, Germany.

OpenAI, the company responsible for Dall-E, is also located in Munich, but Stability AI, the company who makes Stable Diffusion (subsequently releasing the code as open source) is based in London. Getty Images, the company sueing them both, is based in the United States. International copyright law is in play here, and each country has some version of the Fair Use doctrine. Which country’s laws should apply for each part of this case is such a complex question that it may never be properly resolved.

LAION is a non-profit organisation that collects image-text pairs on the Internet. It then organises them into datasets based on factors such as language, resolution, likelihood of having a watermark and predicted aesthetic score, such as the Aesthetic Visual Analysis (AVA) dataset which contains photographs that have been rated from 1 to 10.

LAION gets these image-text pairs from another non-profit organisation called Common Crawl. Common Crawl provides open access to its repository of web crawl data, to democratise access to web information. It does this by scraping billions of web pages monthly and releasing them as openly available datasets.

Secondly, in order for there to be copyright infringement you actually have to copy something. While the LAION dataset does contain images, the Stable Diffusion project used the images but the resulting compiled datasets do not.

The fact that this suit is being fought in an international arena, where copyright law, already a complex landscape, is often murky and unstable as quicksand, suggests that it’s more about appearances than actually winning in court. Getty, a licensor of images, must create the impression that it is doing something constructive about the question of the legality of using research data for generating AI art to avoid exposure to litigation itself. It doesn’t have to actually win.

Faulty Assumptions

The biggest problem with the law suit against Stable Diffusion, Dall-E and Midjourney is that the plaintiffs declare the AIs to be “collage engines” and this isn’t how they work at all.

They can say that, but that doesn’t make it true.

In fact, 5 billion source images will simply not fit in a database file 8 billion bytes in size like the one Stable Diffusion uses. The images cannot possibly be simply stored and retrieved for pastiche in the way they assert, and that’s the foundation of their law suits. The claims of “illegal copying of copyrighted work” fail immediately on this point.

The Fair Use doctrine, regardless of which country’s version you use, is based on the initial premise of file copying or republication of the original images. In point of fact, the Fair Use doctrine, regardless of the country’s legal system applying it, allows copying for reference purposes, which is clearly what LAION was doing. In fact, not allowing the copying of images would break the internet. In order for web browsers to work at all, they must be allowed to make a digital copy of everything on a web page, even if that copy only exists in memory for a brief time. Typically, though, web browsers cache pages to make them faster to load the second time you visit, and it’s very difficult to turn this web browser feature off — so everybody, everybody copies Getty’s images for the purposes of viewing them. It all comes down to redistribution of those images, and apart from the reference purposes application, none of the defendants are actually doing this. Instead, the images are going through a process of loose emulation and are statistically never fully reproduced.

The Filing

The case involving Stability AI was filed in the District Court of Delaware, which is notorious for taking its sweet time about law suits in general. It might be six to nine months before the courts even examine the case to see whether there’s enough there to move forward. It will likely take several more years for the Getty Images case to get through discovery and summary judgment motions before trial.

Exactly what Getty hopes to accomplish isn’t clear. They’re not going to stop the tools from being used, nor put the genie back in the bottle. They might manage to extract some kind of expensive settlement or punitive judgement from Stability AI et al., bad enough to put them completely out of business as a worst case, but I envision few possible corrective measures apart from this.

The Getty case failing on the Fair Use question is frankly just as likely. Getty might be able to point out their watermark showing that their images might have been used, but Fair Use encompasses reference and research purposes very specifically. Getty may be picking a fight they can’t actually completely win. It’s a longshot, given the significant and specific carveout for Fair Use being applied here.

That said, most of the Getty complaint seems to pivot on the appearance of their watermarks on generated images, such that it damages their brand. They may have a point here, but one of the remedies they want is the destruction of all versions of the Stable Diffusion datasets that contain Getty Images content. There are few examples of actual copyright infringement in the initial filing, and you’d think Getty would have done a more comprehensive job of adding these in, because they’re not allowed to make a fishing expedition out of this. Claiming copyright infringement on this order of magnitude is a substantial claim, and it would require substantial initial evidence, and Getty hasn’t got it. And to get it might require that Getty prove that their images can be reliably recreated from prompts, over billions of examples, and that does not sound practical.

It’s open source software, and it’s been released to the world, and will have likely been in distribution eight to ten years before a jury ever delivers a final judgement, so good luck with that. By that time, Stable Diffusion will be so ubiquitous it will have spawned half a dozen different open source versions, and will practically have soaked into the wallpaper. The best Getty can hope for is to put Stable AI out of business, but it won’t stop Stable Diffusion itself. The damage is done, and probably irreversible.

AI Art and Copyrights

It’s important to note here that discussions to the effect that the Copyright Office will not honor AI generated art are factually incorrect.

Despite popular misconception (explained in this article on The Verge), the US Copyright Office has not ruled against copyright on AI artworks. Instead, it ruled out copyright registered to an AI as the author instead of a human.

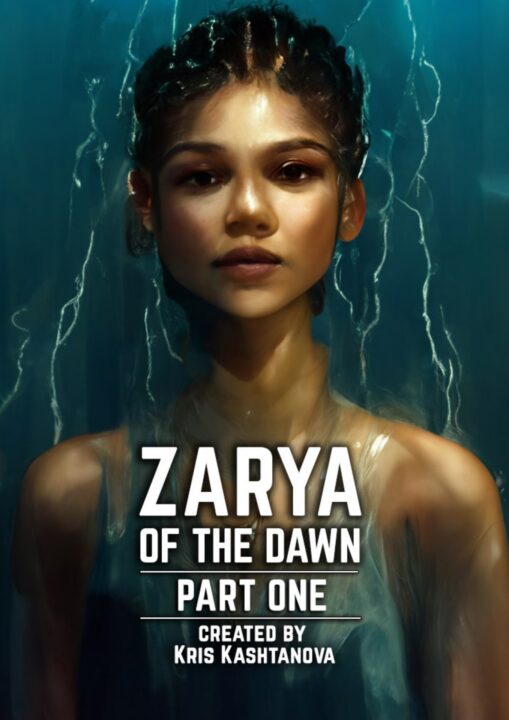

Zarya of the Dawn, which features a main character with an uncanny resemblance to the actress Zendaya, is available for free through the AI Comic Books website. AI artists often use celebrity names in their prompts to achieve consistency between images, since there are many celebrity photographs in the data set used to train Midjourney.

-30-

Gene Turnbow is President of Krypton Media Group, and the founder and station manager of SCIFI.radio. This article is written as a companion piece to David Raiklen’s article on SCIFI.radio, Is Your Software A Human? AI Art in a Human World.